Transfiguration B (Mark 9:2–9)

If you are the image, you are the product.

This is another piece of scripture commentary published originally in The Christian Century. See if you can spot the nod to the Buzzcocks I worked into it.

Listen! And I will tell you a mystery: you are more than the filtered face you present on Instagram or the selfies you Snap to friends, greater than the sum of your snarky replies in the group chat or the videos posted in your favorite subreddit. You are even better than your TikTok dances.

Adults are quick to issue this kind of warning to the kids, especially when body image or self-esteem comes under threat. They’re right to do so, but the grown-ups have their own challenges. A whole person is made of bigger and better stuff than the happy family photos that litter Facebook walls or the loud and cynical political opinions found there and on so many X timelines.

The digital image we present to ourselves seems so real, feels so real, yet we cannot touch it. We exist in it only as representations of ourselves, pixels on a screen. Regardless of the promises of virtual reality, we cannot even experience this world except as passive consumers.

And anything that can be consumed can be turned into a commodity. We are caught in a capitalist society that reduces being to having and having to seeming, according to the French theorist Guy Debord. That was a dire prophecy when he issued it in 1967, and it has become only more relevant in the age of social media. Our global culture has become obsessed with public image, or as Debord puts it, we have allowed images to mediate our relationships with one another. If you are the image, you are the product.

The symptoms of this sickness are everywhere, if you know where to look for them, from identities built on allegiance to commercial brands, to the fractured mental health of teens trying to keep up appearances, to politicians selling not policy ideas but a tough-guy image or signals of in-group identity.

Social media may not even be the worst of it. Artificial intelligence is used to construct faked nudes for revenge porn. And in the recent screen actors’ strike against Hollywood studios, the executives made a ghastly proposal that would allow them to scan an actor’s likeness and use it to create a digital character that could be used in perpetuity, without compensation, without even permission required. Once you possess someone’s image, you own them in some nontrivial sense, and so Debord’s chain works in reverse: to seem becomes to have, and to have becomes to be in the life online.

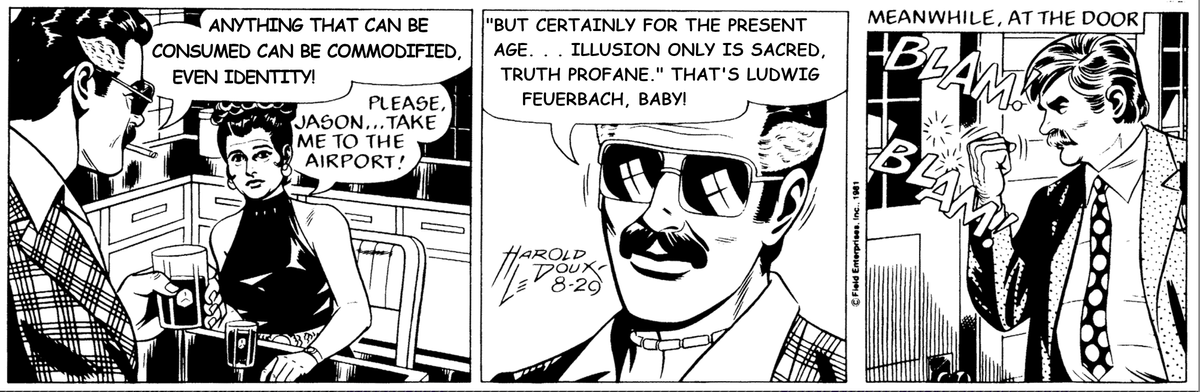

Debord’s preferred response to the reification of image was détournment, turning spectacle back on itself by appropriating its images and reconstituting them in ways that undermine the contentment of easy thinking. (Think Lucky Luke comics spouting Communist theory or the verbatim words of George W. Bush repackaged as poetry.) Indeed, much of the playful use of text and imagery in social media can be read this way. If we cannot escape the reign of the image, we might still find some kind of authenticity in derailing the commodified meanings assigned to it.

Interestingly, The Society of the Spectacle, Debord’s manifesto against image-dominated culture, opens with a quote from Ludwig Feuerbach: “But certainly for the present age, which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, representation to reality, the appearance to the essence . . . illusion only is sacred, truth profane.”

Feuerbach meant that as a stinging criticism of Christian faith. But he failed to reckon with the way in which Christ himself plants a flag in reality on Mount Tabor. Jesus’ appearance with Moses and Elijah is no stage show. Nor is it an illusion or a signification. In fact, the Transfiguration is not an appearance at all. It’s more like dropping the true and authentic Jesus in our laps and making us deal with it. For a brief, proleptic moment, the disciples see Jesus as he is, in his almost complete post-resurrection form. This is all being and no seeming.

Jesus lacks only one thing: the wounds of his death, the holes in his hands and side that Thomas will be invited to use as verification of his identity. Like the post-resurrection stories it anticipates, the Transfiguration is a reality that can be seen and felt and touched and tasted, even if only for a moment. And like them, it is a promise of a life to come.

Despite its cinematic potential, what Peter and James and John see that day is not a reality that can be neatly packaged for resale. It will never go viral. Instead, it invites readers into an unmediated and unmediable relationship.

That’s because the question, “Who is Jesus?” cannot be answered without asking, “Who is Jesus to me?”—which in turn requires the question, “Who am I?” Paradoxically, the revelation of Jesus in his sovereign glory forces us to decide not who we want to seem to be but who we are. That might be theology through anthropology, but it is also an ever-fresh mystery that cannot be contained within a world bounded by ones and zeros and emojis.