How Merle Haggard Saved My Soul

Haggard’s greatest gift may have been his faith, even if nobody seems to be able to pin down his religious practice.

Originally published April 12, 2016 in Religion Dispatches

I raised a glass of George Dickel in honor of Merle Haggard the other night. The country legend, who died last week on his 79th birthday, was an enthusiastic endorser of this brand of Kentucky bourbon, you see, until they sold out to a corporate conglomerate. It was an appropriate match. True, the drink is smooth on the surface, where Haggard was gritty, but underneath, the man and his drink share strength and fire. You don’t water down the good stuff.

It’s only now Haggard’s gone that I realize how much I owe him.

The first obvious gift was the Bakersfield sound, which Haggard pioneered along with Buck Owens. Without Bakersfield and Haggard—rougher, twangier, and more direct than Nashville would allow—there would be no pre-Rubber Soul Beatles sound (go back and listen to it again), no Gram Parsons or Sweetheart of the Rodeo, no Steve Earle, Dwight Yoakam or Sturgill Simpson, arguably no X or the Replacements (no, really, listen to it all again). Haggard’s band, the Strangers, were a tight band, more precise and fluid than anybody this side of Captain Beefheart or all but the best bluegrass combos.

But then too, Haggard generously taught the sort of iconoclasm it took to listen to him, to show up on campus in the early ’90s with one his CDs tucked under your arm, or an LP from George Jones or Dolly Parton. I learned from him not to give a shit if people didn’t appreciate great music because it carried the “country” label. There’s a reason John Doe covered “Silver Wings” in the ’80s. He knew a well-constructed song when he heard one, and a kindred rebel soul.

As Haggard’s music sank in over the years, I learned too about being unapologetic for a humble background, or an unpopular opinion. He made it possible to embrace the artist-as-crank, and for that I will always be grateful.

Everybody talks about Haggard’s integrity. He called it like he saw it—even when he later came to regret it, as with 1969’s anti-hippie anthem, “Okie From Muskogee,” a song that got him pigeonholed as a reactionary for the better part of 30 years. But then he opposed both Gulf Wars, telling Time in 2007:

I supported George W. I’m not exactly a liberal. But I know how that Texas thing works, who those oil folks are and what they wanted in Iraq. I’m a born-again Christian too, but the longer I live, the more afraid I get of some of these religious groups that have so much influence on the Republicans and want to tell us how to live our lives.

Haggard also took up for Obama in 2012:

I don’t think it makes much difference who the president is. I think there was a big ball rolling before he came into the picture. He kind of did what I do. I didn’t do anything. He hasn’t done anything that I can see that’s made any real difference. I think he is a fine gentleman, and they treated us real well when we were up there at the Kennedy Center (Haggard was a Kennedy Center honoree in 2010), and I am not going to badmouth him. I think he has the next four years wrapped up. He has done some good. He got Osama bin Laden. That is a real big plus.

Now on the home front, it is kind of fiddling while Rome burns. We are in trouble economically. I don’t think we can blame it all on one black man. I think we spent 50 years getting ourselves in trouble, and it may take a long time to get ourselves out of it. It is going to take more years than I got left.

(Lest you think he went soft in later years, check out what he had to say about the gold standard and U.S. military bases in the very next paragraph of that interview.)

Haggard’s greatest gift may have been his faith, though, even if nobody seems to be able to pin down his religious practice. His mother was a member of the strict Church of Christ, and Haggard himself often claimed a generic evangelical faith, albeit the kind that was mostly reflected in the occasional “prayer being mumbled under our breath,” as he told CNN.

His religion found more expression in the music. Haggard once cut a gospel album pulled from performances at churches (he basically hijacked a Sunday morning at Big Creek Baptist Church), the prison chapel at his alma mater San Quentin, and a rescue mission in Nashville. It’s a masterwork of spiritual and musical generosity: he makes space on the album for pastors’ prayers and rambling introductions, the prison choir, and a duet with his wife Bonnie Owens.

Where other country artists would have tried to wring every last drop of schmaltz out of the gospel standards, Haggard goes low key. I’ve never heard a version of “Amazing Grace” that was less of a tearjerker.

At times, Haggard came across like a prophet. In his great psalm of repentance, “Mama Tried,” he unleashed a famous lament:

I turned 21 in prison

doing life without parole

That leaves only me to blame

Because Mama tried

Haggard did actually spent his 21st birthday in solitary, doing hard time for attempted robbery, a felony conviction later pardoned by Ronald Reagan. But the man knew what he spoke of.

In sharp contrast to the bleakness of “Mama Tried” stands the deep hope of the greatest Christmas song ever written, “If We Make It Through December,” with its trusting assertion “I plan to be in a warmer town come summertime.” Haggard rarely name-checked the Lord in his songs, but he didn’t need to. You couldn’t listen to a line like that without knowing the source of his confidence.

Haggard laid it all out on the line, like an Old Testament preacher. He spoke about disrespect to disabled veterans in “Me and Crippled Soldiers,” race (“Irma Jackson”), the effects of alcoholism (too many to mention, but “Tonight the Bottle Let Me Down” was a particular standout), relationships (“Carolyn”), and above all else the grinding reality of poverty, as in “Hungry Eyes”:

Mama never had the luxury she always wanted

But it wasn’t because my Daddy didn’t try

She only wanted things she really needed

One more reason for my Mama’s hungry eyes

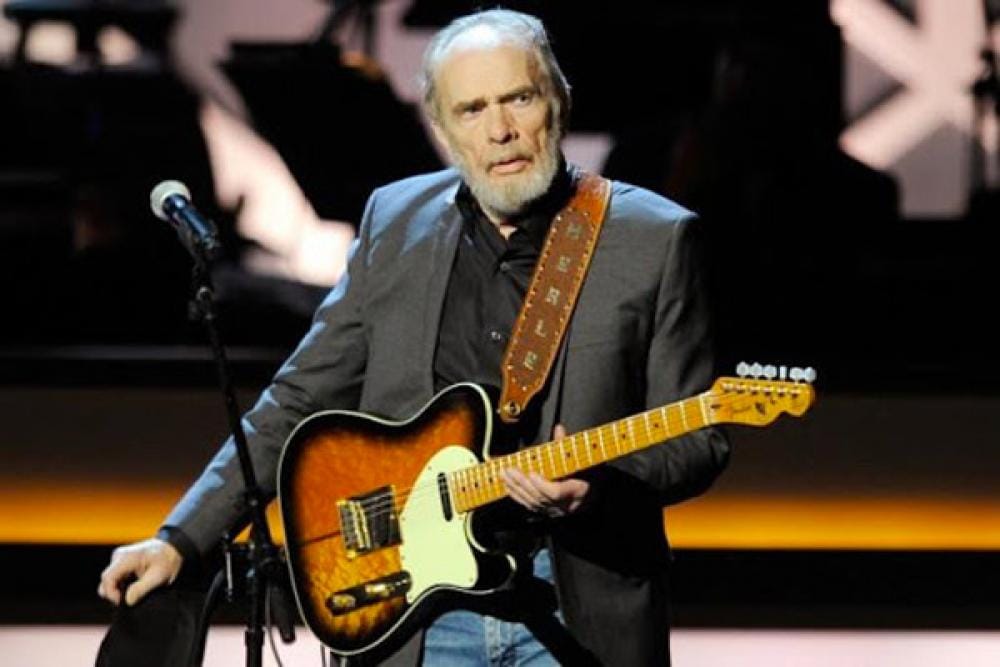

Like a six-string Steinbeck, Haggard kept calling his listeners back to the barely-fictionalized Okies he knew from his childhood growing up in a boxcar in Bakersfield, and he did it with a natural “appreciation for the immense dignity of the poor,” to steal a line from Pope Francis. His church may have been a concert stage, and his pulpit a Fender Telecaster, but Haggard’s faith was always centered on humanity—and it always believed in redemption, whether that was freedom from booze or release from being dirt poor.

I owe a lot to that faith, not least of which was my own salvation, in a way. At a time when I was drinking too much and not finding enough direction in life, a friend slipped me a tape of Haggard—among many other country stars—singing gospel. It finally occurred to me one night while smoking a Lucky Strike that I liked the album not just because the music was so good, but because the message was something I needed to hear. That propelled me into an adult faith, and from there into seminary and a career spent mostly serving a lot of people who looked and sounded like Merle Haggard.

They think my love for him is a joke. I don’t care.

So here’s to you, Mr. Haggard. God bless you and keep you, and thanks for everything, not least the excuse to drink this next round of Dickel—and the one after that.