How to Love Your Enemies, And Other Impossibilities

Luke 6:27-38

The 16th-century theologian, dictator of Geneva, and generally terrible person John Calvin said that humans ought to be able to look at the physical world and discern from it signs of God and God's intent.

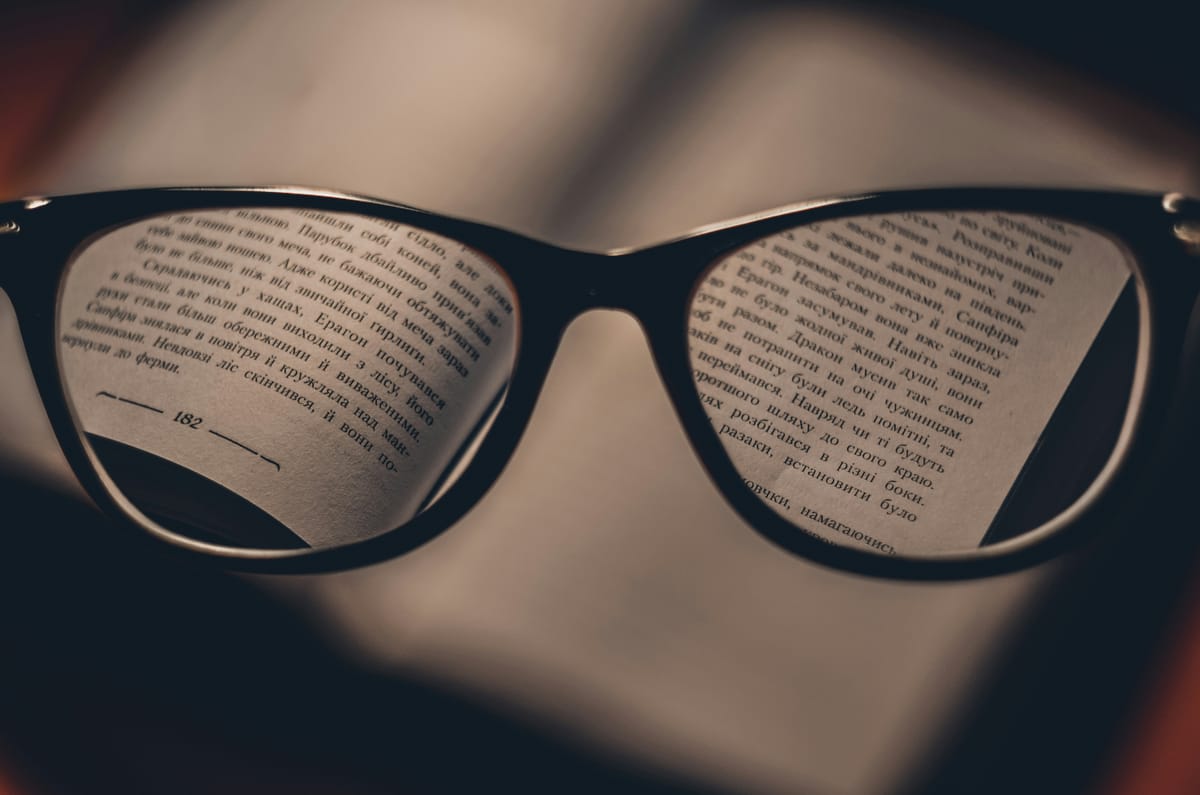

Unfortunately, as Calvin believed, humans are too stupid to read the signs. (Sadly, this is not much of a paraphrase. Calvin was not noted for his high opinion of human nature.) So God gives scripture to serve as eyeglasses, as it were, to understand the world around us. Elsewhere, he's more specific, saying that humanity is like a bunch of old men who can't understand a word of what a book says until they put on their reading glasses. I am sorry to say that's an analogy I understand all too well these days.

The more I go along, the more I think Calvin had a point. I would say scripture provides us with a lens for seeing the world aright, rather than the lens. But I very much agree that humanity needs some form of moral vision correction.

In fact, I would go a step beyond Calvin to say that scripture not only helps us to see reality correctly, it helps us to build reality correctly, to see in the first place the world as God wants it to be, if you're a believer, or to see the world as it could be, if you're not. Then to go beyond seeing to creating. Scripture anticipates the reality to come, and by giving clear vision of what could be, sets into motion the realization — the making real — of that vision.

You can't build it until you can see it, and you can't see it until your way of looking at things changes

I know that's a dense and chewy couple of sentences, so let's say it's sort of the Field of Dreams principle: you can't build it until you can see it, and you can't see it until your way of looking at things changes.

Nowhere is that model more important than when we come to some of Jesus' "hard sayings," such as: love your enemies. This is an ethic that the commentaries variously describe as "difficult," "impossible" and "oxymoronic." By definition, an enemy is someone detested, resisted, combated at every step. To put it simply, IT'S FREAKING IMPOSSIBLE TO LOVE YOUR ENEMIES. And yet, that's exactly what Jesus wants his followers to do.

To make matters worse, he has just given Luke's version of the Beatitudes:

‘Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.

‘Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled.

‘Blessed are you who weep now, for you will laugh.

It's not just that disciples should be on the side of the poor, the hungry, those who weep, and so on. It's that they should understand that God is on the side of those people. And it's not just that they should understand whose side God is on, it's that they should learn that this is the way God sees the world, creates the world, and so should they. How do disciples come to do that? By loving their enemies, by doing good to those who hate them. This is more than just having warm feelings, as you might expect. It's about taking concrete steps.

Jesus provides some examples for his listeners: bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you, offer the other cheek, let people take your things without resistance. None of that is strategic. None of it is part of some larger project, or a means to an end. It's just: be kind, no matter what. Don't fight back, no matter what. In giving these instructions, Jesus undermines the logic of revenge, of endless tit-for-tat, grudge keeping, getting even.

He also reverses the logic of reciprocity, that we do nice things for people who do nice things for us, and evil things to people who do evil things to us. That's the prevailing social more of Jesus' day, and he tosses it aside without so much as a second thought.

So you love those who love you? Bless your heart.

Understanding all of this helps us to make sense of the next part of the lesson. Most of us have learned the Golden Rule as a kind of all-encompassing moral standard: do unto others as you would have them do unto you, and you'll be a good person. It's present in most, if not all the major religions. And yes, it makes an easy-to-remember, easy-to-follow lesson. There's a reason we teach it in Sunday School.

But Jesus establishes the Golden Rule as a bare minimum for his followers. His basic rationale goes back to that bit about reciprocity. So you love the people who love you. So what? Even the sinners can do that! If you were really hardcore, you'd throw a full bottle, and you were really a disciple, you'd love those who hate you. Jesus gives three examples to illustrate his point: loving, doing good, lending. Each example comes with a tag line, "What credit is that you?" Luke Johnson says it's almost tempting to translate it as "What sort of [spiritual] gift is that?" You can almost feel the sarcasm dripping off the page: So you love those who love you. Bless your heart.

If you can go above and beyond the ordinary morality, says Jesus, "your reward will be great." His followers will become "children of the Most High," in that they will be kind to the "ungrateful and the wicked" just as God is kind. Matthew has Jesus call on disciples to be "perfect as your Father is perfect," while Luke depicts him as saying "Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful." Either way, the message is clear. The ultimate goal of Christian life is to imitate God, to love as God loves, as difficult as that may be.

The rest of the reading takes up a different lesson, so I will let it go, other than to note that "the measure you give will be the measure you get back" means something like "The measure you use will be the same one God measures you by." Be better than your enemies!

God is merciful and will look kindly on doing even a little bit.

How then do we get anywhere close to fulfilling this impossible command to love our enemies? First, let me say that while Jesus probably really did want people to live out that commandment literally, he was also probably realistic enough to know that they would fail the attempt. The point, I think, is in the trying, not the full completion. God is merciful and will look kindly on doing even a little bit.

Second, we should remember that the ethic of loving your enemy doesn't map well onto a broad social application. That's especially true in the modern age, where our enemies tend to be abstractions, rather than people we have to deal with face-to-face. Democrats hate Republicans! — but you know, Uncle Bob has some redeeming qualities. Republicans hate Democrats! — but that family down the street, they're not half bad. Once we see our enemies as people, they tend to stop being enemies. That's not a guarantee that everyone will get along, of course. But it at least makes things better.

And as Reinhold Niebuhr correctly noted, the more people you are responsible to and for, the less room you have to implement your personal morality. I can forgive somebody who punches me. The president doesn't really have that option when the nation is attacked.

So how do we live up to Jesus' exhortation to love our enemies? I think the key is to step out of a self-centered, rationalistic way of thinking, one that continually asks what we can use things or people for. That is to say, we shouldn't ask "What good does it do me to love my enemy?" Or even, "What good does it do my enemy to be loved by me?" This isn't a transaction, we're not trying to get anything out of the deal.

Instead, following the thought of the Japanese philosopher Keiji Nishitani, we need to embrace first a radical form of objectivity, of simply accepting people for who and what they are.

We have to see our enemies as they are, without reducing their complexity

Let me give one good example of what Nishitani has in mind. I heard once of a German man who had lived through the Nazi years, maybe served in the Wermacht in World War II. Ever after this man could not abide people going on about how evil Hitler was. Not because he was a fan! But because the minute you turn Hitler into a demon rather than an ordinary human, you start to lose detail that you need to truly understand his impact on society. And the minute you forget that Hitler was only one man, you forget the system he was part of, the system that produced the horrors of the Holocaust.

So we have to see our enemies as they are, without reducing their complexity or turning them into a caricature to manage our own anxiety. That is certainly not an easy thing to do.

We also have to turn our attention from ourselves to the wider web of connections in which we exist, physically, socially, ecologically. We have to ask as Nishitani does, For what purpose do we ourselves exist in this interconnected reality?

Mind you, that question isn't "What's my purpose in life?" It's more like "Why am I here, as this particular node in the universal network?" In other words, we must turn our focus from doing to being. Despite Jesus' concrete examples, the question of how to love our enemies isn't ultimately about what we should do. It's about who we should be. Jesus answers that question directly: be merciful, as God is merciful. Which is to say, compassionate, empathic, alert to suffering and willing to alleviate it. That quality, chesed in Hebrew scripture, which we normally translate as "steadfast love" or "loving-kindness", is central to God's character.

Once we embrace the idea that we are meant to be people who imitate God's character, both the doing and the reality begin to fall into place. That isn't a lesson for Christians only, of course. Jews and Muslims who worship the God of Abraham certainly have a direct path to fulfilling the command: same God, same calling to imitation, just without the Jesus part.

We can choose to be better people.

But even for people of a different religion, or no religion, there is a useful lesson. If who we as humans are meant to be are loving, merciful, compassionate people, it means that we are free to walk away from eternal conflict and hatred of our enemies.

We can choose to be better people. We can choose to be ourselves.

The promise for Christians, and Jews and Muslims, is that in becoming people who love as God loves, we take part in God's being, just as children take part in the being of their parents. But even without that participation, seeking to be the people who love their enemies gives us a different way to see the world, a different way to see what the world and we ourselves are meant to be. I for one think that way of seeing is very, very much needed these days.

You may think that I am wearing rose-colored glasses, or that I am wrong or stupid. It's okay. I will love you anyway, or do my best, impossible as it might be. Amen.