Paul knew something about being an obnoxious weirdo

I occasionally write commentary for The Christian Century. This essay on 1 Corinthians was posted on January 29, 2024. I daresay you're not going to see many scriptural reflections with a lede like this.

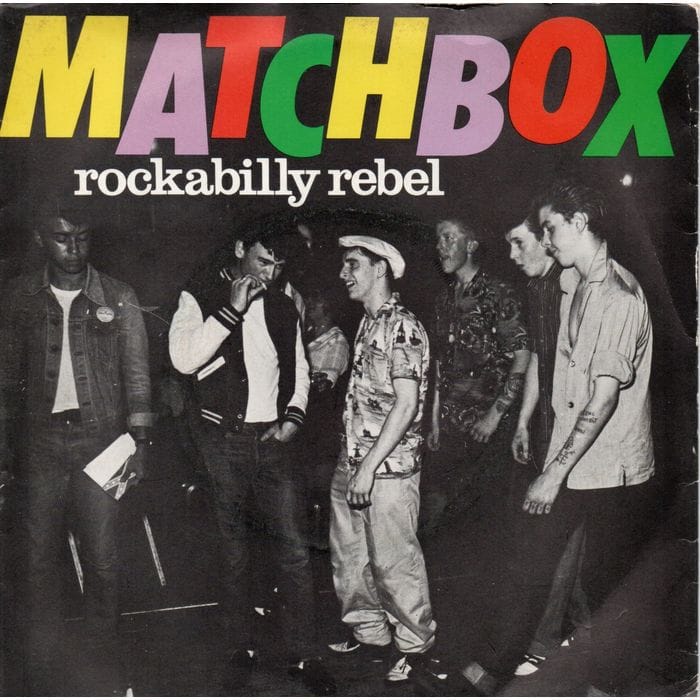

Forty years ago, I was a punk. Or more properly, a rockabilly punk, with a slicked-back pompadour and the finest suits and ties five bucks could buy at Ragstock. After years of being crushed by the social hierarchy that only a middle-class, overwhelmingly White, mostly suburban middle school in the early 1980s could produce, I was determined not to follow the rules. I reveled in the sheer, obstinate, and not a little manic fun of tweaking high school’s preppy norms. I was, in short, an obnoxious weirdo.

These things mostly don’t last, of course. I kept the musical tastes but ditched the clothes by the time I made it to college. For years, I dressed as blandly as possible—perhaps to make up for past excesses, perhaps to fly under some kind of radar only I could detect.

And yet, the punk ways survived just below the surface. Soon after I left my last congregation, I turned 50 and dropped the professional gear for lots of flannel and a denim jacket. I see old guys like me at shows and have to laugh. They’re easy to recognize by the uniform: a flat cap covering a balding pate, a long beard, a band T-shirt (always black), craft beer in hand.

The point was never to be unique, though, nor was it to live the lifestyle forever. Beyond contrarianism, the idea was always to assert control over one’s identity, to choose for yourself who you wanted to be, even if that wound up being the same narrow dad tropes that everyone else adopted. Better to be an obnoxious weirdo than to let somebody else dictate who I was.

Paul, as he so often does, got there first. That man knew something about being an obnoxious weirdo, and he had fun with it. In the midst of a letter to the church at Corinth defending his ministry and himself, the apostle rattles off a list of identities he’s adopted over the years: Jew, gentile, a person bounded by Torah or not, the “weak.”

There is not a personality crisis here. Paul grew up in cosmopolitan, well-educated settings. He had certainly been around Jews, Greeks, and Romans enough to know how to get along with people of different cultures. His “becoming as” feels like a rhetorical flourish. It’s still the same Paul in all the different phases, but adapted to his settings.

And though he uses the language of commerce, his reinventions are never simply about making a sale. Where the “strong” of Corinth were inflexible and smug in their identities, Paul was willing to become like the people he evangelized so that he could walk with them.

The profit of this enterprise, such as it was, came from the opportunity to share the gospel. Unlike so many evangelists, Paul was not interested in bringing his culture to benighted people. That’s why he was so willing to shed his baggage and adopt other customs. The point was the message, not the surface form it came in.

There’s humor in how Paul delivers this message to the Corinthians, a kind of reverse snobbism aimed at the strong. Like any good punk, Paul may seem to be a loser on the surface. But he has chosen the course of his own life, and he is satisfied with the results, no matter what anyone else thinks.

Jesus, for his part, took a different path. He was never a conformist: by some tellings, his fashion sense was a T-shirt and jeans among the business suits of his day. But by the depictions of the gospels, he was who he was all along, never surrendering to the pressure to be someone else, even from Satan. In fact, Jesus seems to have been exceptionally differentiated. When the people of Galilee want to box him into his healing ministry, he tells his disciples that it’s time to move on, the better to preserve his calling to preach.

Modern consumer culture presents far more opportunities to reinvent oneself than were ever available in the ancient world. It would only take a few keystrokes to make myself into a tweedy academic. A couple hundred dollars and an hour or two at the local Fleet Farm and I’d fit right in with the working-class camouflage enthusiasts in the area. But there is truth in one of Henri Nouwen’s sayings, that the features most unique to ourselves are in fact those we hold most in common with other people.

The surface features of identity are flimsy and easily manipulated. What Paul and Jesus knew was something deeper: that who we are is not a matter of the clothes we wear, the music we listen to, or the social media we participate in. Our identities are defined by who we love. Phases come and go. So does nonconformity. The real work continues throughout life, even for the punkest of the punk: to maintain the freedom to love who we need to love, and so become ourselves.