Wisconsin made me risk my life to help people vote on Tuesday

If I die of this stupid virus because of this ill-advised election, you have my permission to politicize my death.

If I die of this stupid virus because of this ill-advised election, you have my permission to politicize my death.

This is an "as told to" opinion piece created from an extended interview with editor Sophia Nguyen and published April 7, 2020 in the Washington Post. I wouldn't ordinarily include such a piece, but it does give some sense of how we framed COVID issues at the Campus Election Engagement Project (now Civic Influencers).

Usually, volunteering to help run polls for a state election is a relatively small, painless way of participating in the democratic process. Polling places open early, the hours can be long, and people might grow impatient if the line moves too slowly — but you’re helping your fellow citizens exercise their franchise, and everybody goes home feeling good.

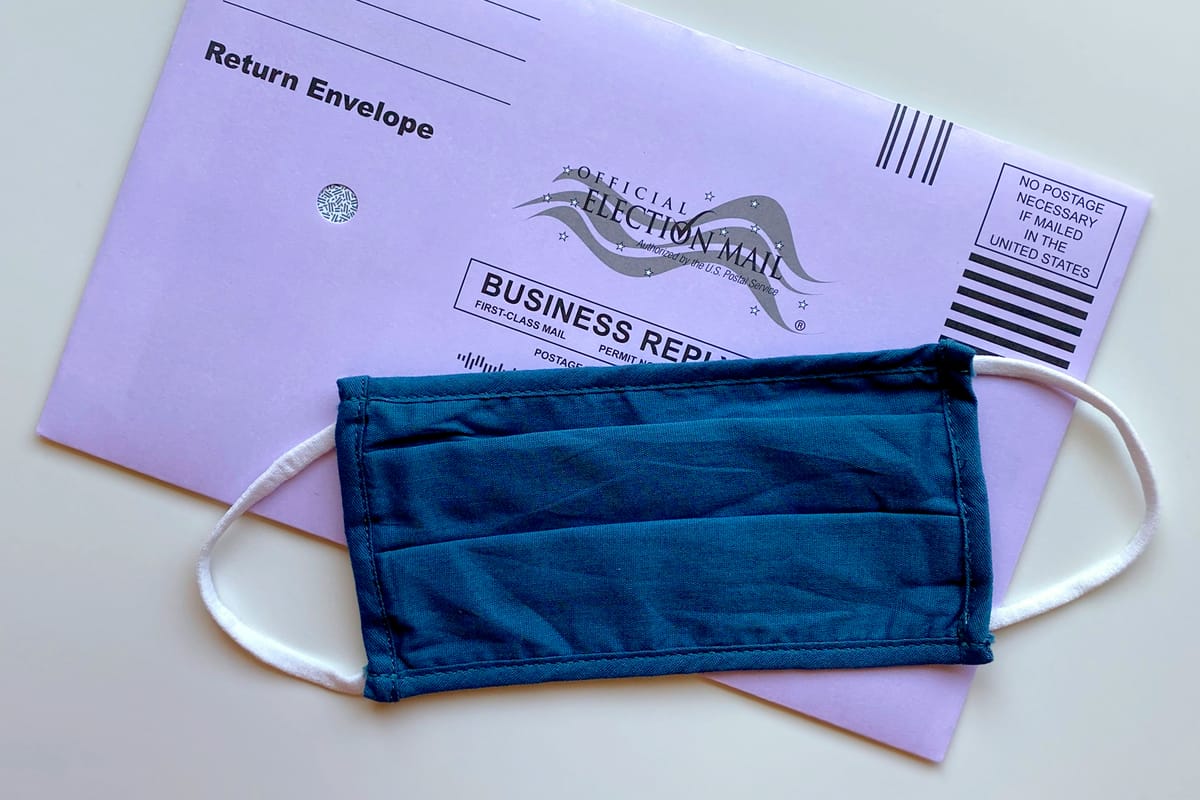

But during the coronavirus pandemic, participating in Tuesday’s election in Wisconsin has taken on ridiculously high stakes. Republicans here insisted — and the Supreme Court agreed — that the election go on as scheduled despite the outbreak. This was a huge public health risk, and I’m furious at our leaders for putting voters and poll workers in this position.

Even though I joke that there are worse things to die for than defending the right to small-D democratic civic engagement, I’m 51 and in pretty good health — the chances that I will catch covid-19 and die are fairly remote. But to me, the elevated risk feels like walking into somebody’s living room and seeing a loaded gun lying around in plain sight. The chances that they will pick it up and kill me are slim, but they should really put it away — I’d rather not play the odds. Voting in Wisconsin was dangerous today, and it didn’t have to be.

A few weeks ago, my wife and I read in the local paper that many towns would be short of poll workers because of the pandemic. We signed up. Our city sent us a training video about how to check in voters and process ballots, including a segment on health precautions. But as the coronavirus took hold throughout the country — and as state leaders continued squabbling, in special legislative sessions, emergency executive actions and court rulings — I grew uneasy about whether it would be safe to volunteer. The state’s coronavirus case count climbed to more than 2,000.

I hoped that our officials, like their counterparts in more than a dozen other states, would decide to postpone the in-person vote and expand access to mail-in ballots. We’d already been under stay-at-home orders since March 25. But late Monday night, Republicans won the final legal skirmish, and it was clear that the election would go ahead. I told my wife, “You know, I would feel better if only one of us were doing this, and I really would feel better if it were me.” Fortunately, she agreed.

When we poll workers showed up early Tuesday morning, the city clerk gave us each some gloves (which I quickly gave up on, since they made it hard to write) and a surgical mask. Impressively, we each got our own bottle of hand sanitizer. At the first table, we set up what looked like a deli counter sneeze guard made of plexiglass; people slid their IDs underneath to be checked. At the next table, we handed out ballots. (No sneeze-guard there, though, because it was relatively low-contact.) Each voter got a pen to sign the poll book and fill out their ballot; afterward, they dropped the pens in a bucket, and we blitzed them all with sanitizer so they could be used again.

I live in Fond du Lac, a city of about 45,000 people. My polling station, a high school gym that smells like wood polish, was pretty calm. By the time I took a lunch break, we had about 60 voters come through; my ward manager estimated that absentee ballot requests have almost tripled compared with previous years. My nerves settled somewhat as I went about my work. But I kept reminding myself: Just because everything looks normal, and feels normal, doesn’t mean that everything’s okay. People — many of them senior citizens, hellbent on voting even if it was against medical advice — took an unnecessary risk just by showing up. Areas like Milwaukee had hundreds of people lining up to vote.

Our situation was so unnerving in part because it’s easy to imagine pandemic conditions lingering for the November elections — or returning in some other form, some other year. We want to trust our elected leaders to safeguard the democratic process during a public health crisis. Wisconsin shows that some of them won’t.

I don’t object to the actions of the Wisconsin legislature and the conservative-controlled court because those politicians are Republicans. I’m objecting because those actions will exclude people from the franchise. I didn’t work at the polls, potentially putting my health on the line, for any one political party. I did it for everybody: Democrats, Republicans, the unaffiliated. We poll workers showed up not out of whatever party loyalty we may have but out of a more basic principle: We want to help our fellow citizens make themselves heard.

If I do die of this stupid virus because I took part in an ill-advised election, I want people to know: You have my complete permission to politicize my death. Push for mail-in ballots. Push for voting reform. Make sure every anti-democratic politician who callously risked their constituents’ lives has to answer for it.